I have been thinking a lot—probably too much—about names for our upcoming kid. While her first name is still very much in the air, we’ve settled on a last name. In this post, I’ll go over what I saw as the main options and considerations in making that choice.

The classic patrilineal thing

I’ll begin with a feminist rant.

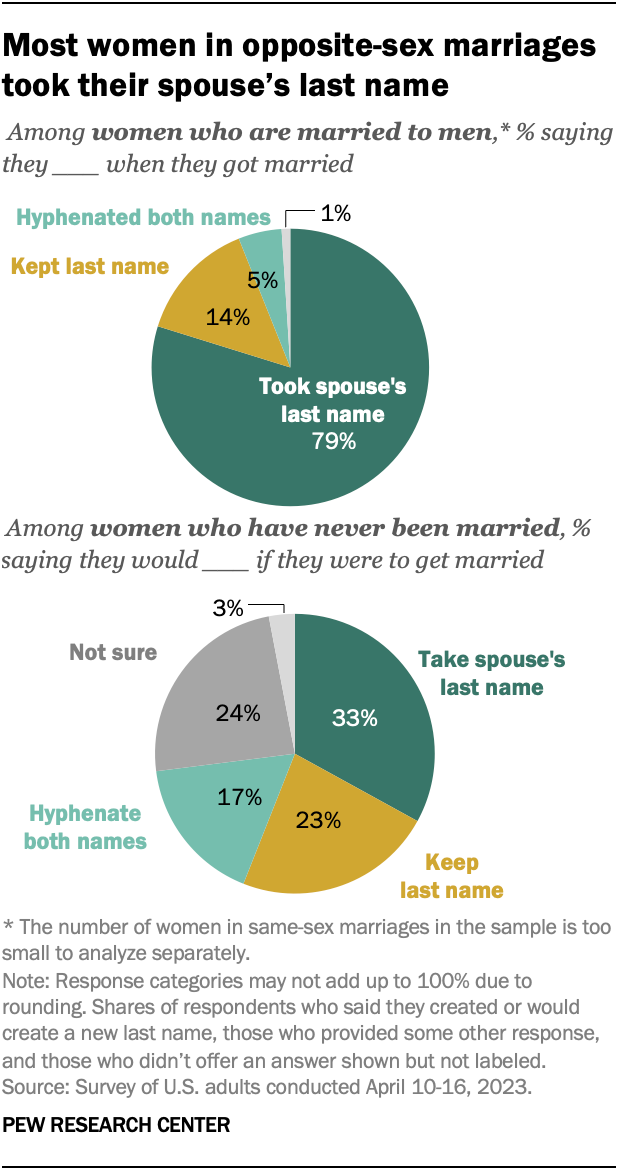

Among heterosexual couples in the United States, about 96% of children have their father’s last name1 and 80% of women take their husband’s last name when they get married. This strikes me as bizarrely patriarchal.

Most women are liberal, and among liberals, other equivalently explicit prescriptions or symbols of female submission in marriage are blasphemous. Liberals do not suggest that women should always agree to sex, or put their husbands’ families above their own, or act as domestic servants to their husbands, and so on. They’ve even staged out the term “Mrs”.

But for the most part they go along with this tradition that designates the father head of the family unit. Bizarre.

There are two things going on here: first, the woman changes her name to her husband’s upon marriage. Next, they pass that name—the father’s family name—down to their kids.

The first step makes me squirm. It’s reminiscent of the tradition where a bride’s father “gives her away” at her wedding. At our wedding, both Austin and I walked with both of our parents, but the priest still instructed my Dad to literally pass my hand to Austin as though I were incapable of moving freely. Women are not objects to be passed between men! We are not owned by our fathers (at least not more than by our mothers and not by the time we get married) and we’re not owned by our husbands! My Dad had no right to give me away! Now that we’ve left behind the material reality of female subservience that these traditions represent—now that women can own land and get their own credit cards and freely file for divorce—shouldn’t we give up the weird patriarchal traditions, too?

Still, I get that this is the default thing and it’s nice to share a family name, so whatever, changing my name to match my husband’s is not inconceivable.

What is inconceivable is giving my kids their father’s name without taking it on myself, as it seems about 16% of women in the US do, and as is traditional in e.g. China, Korea, and Italy. I am not one to poo poo all remnants of the patriarchy—we are animals, and like all other animals, the males and females of our species will be more inclined toward different roles on average. I am not bothered by the fact that in most families men make more money and women do more childcare. But that’s precisely what bothers me so much about giving kids their father’s name: women are, on average, bigger contributors in the home and in the family than men. Children tend to be closer to their mothers and their maternal extended family, perhaps because their mother and her mother and sisters tend to do the most childcare. It seems so wrong that men put less into their children than their wives, which helps them acquire more achievements to their name through their careers, and then get to claim the fruits of their wives’ labor (haha) by labeling their children with their name. To clarify, I do not resent the work I will do for my kids, just as Austin does not resent the work he’s put into Manifold. Still, he would be rightfully upset if tradition took away his cofounder title on account of some arbitrary characteristic of his. That’s how it would feel for my kids not to have my name.

End rant.

There are some advantages to this custom, actually.

One justification for it that I find more palatable is that in addition to giving the father credit, his name gives him responsibility. Mothers don’t need their names on their kids because it’s usually already obvious who a kid’s mother is—she’s the one from whom the baby emerged, and she’ll get credit and take responsibility regardless of the kid’s name. If fathers are actually less likely to leave their family if their kids share their name, then this seems worth it.

This system also lets everyone have a single name that is shared with all of their immediate family members, and it ties the family to (some of) their ancestors.

If you like those benefits but not the sexism, you could reverse the tradition and have husbands and kids take the mother’s last name instead, though I’m generally against just reversing sexist things to be sexist against men instead in the name of feminism.

Still, depending on circumstances, either way could make sense: if the father isn’t involved, or if he’s estranged from his father so isn’t as attached to his last name, give the kids the mother’s last name. If the father’s last name sounds better, or is from the culture that the kids will associate more closely with, give them the his last name.

This flexible solution sounds nice when the case is clear-cut, but it doesn’t work as a norm: what if both parents like their families and their names? Are they to hash out who is closer to their family or whose family name sounds prettiest? This seems dangerous.

Multiple last names

This is the hispanic tradition and is the most common choice among gay couples. In hispanic cultures, this usually means that everyone just has two last names, the first being their father’s first last name and the second their mother’s first last name. For gay couples, this usually means hyphenating the parent’s names.

This looks egalitarian and means everyone in the family can share the same last name!

But this doesn’t eliminate the hard choice, it just postpones it. The hispanic tradition is actually still patriarchal: the names that kids get from their mothers are from her father’s side, and the names they pass down to their kids will be from their fathers side. In any system like this, one parent’s line will need to be cut eventually, or else kids four generations down will have sixteen last names.

Also, even with the eventual cut, everyone has a longer and less convenient last name.

Portmanteau

Another approach is to combine the parents last names into one word, which is egalitarian, keeps the names short, allows the whole family to share a name, and gives people some freedom in choosing a name they like the sound of.

As you can see from the above example, this system doesn’t keep families tied together for that long: by the end, we’ve lost most resemblance to the original names, and have acquired a resemblance to a supermarket chain. This cuts against ancestor respect/worship, which to me is a downside: our ancestors are responsible for our existence and often for our high standard of living—they have done more for us than we can repay them for directly. Remembering them, keeping their names, creating a legacy under those names, and passing them down seems like a nice gesture. Basically, it’s already unfortunate that the patrilineal system cuts us off from our matrilineal ancestors, and this system does worse by cutting us off from all ancestors.

Completely made up

This has the same upsides as the portmanteau, and the same downside of cutting family lines, just more extreme. Maybe that’s fine though—last names didn’t use to always be about family, but were sometimes tied to professions, like Baker, Weaver, and Smith. In the age of the internet and gene sequencing, family history should be easy enough to track without name sharing, and we can pay respects to our ancestors in ways other than passing down their names.

This system also has the huge upside of total creative freedom: you can pick a name that resonates or that sounds beautiful.

My favorite norm: split the kids (or grandkids)

Another option is to split the kids, giving some kids one parent’s last name and some the other parent’s name. Apparently this is relatively common in China nowadays.

My favorite version of this is to give girls their mother’s last name and boys their father’s last name. For heterosexual couples with biological children, which covers most families, this is so elegant. It means a woman’s mitochondrial DNA maps to her last name, and a man’s Y chromosome maps to his, and both matrilineal and patrilineal lines are easily trackable. It’s sustainable, egalitarian, and doesn’t cause conflict between parents.

Non-heterosexual couples (or those who just don’t like the gendered-ness of my proposal) could instead alternate children, or they could split them by sex but assign parent names to be either female or male arbitrarily. And once we figure out in vitro gametogenesis, they too could match last names to gametes for biological elegance! In the case of polyamorous families…I don’t even know, probably arrangements are too varied to even have a meaningful norm.

Obviously this system as laid out above has the major downside of causing a family unit to not share a name, but if you want to trade concision for unity, you can combine this with the multiple last names approach. Specifically, upon marriage, each spouse adds the other’s last name, and later they give all of their children both names. But on the next generation, when their kids get married, the women keep their mother’s name and the men their father’s and pass those names to their kids, like in the diagram below.

Families still have to choose whose name goes first, but this can be done on a case by case basis, based off of which order sounds better. Or via coin flip.

What Austin and I plan to do

Counter to my strong endorsement of the “split the kids” method (and the fact that it’s what my parents did, though not by gender), we plan to go with the portmanteau, mostly because we like the mix of our last names better than either of them individually. We both have common names which make us not very searchable, and I don’t love my last name—the way it sounds, that usernames are always taken, and that it left me the odd one out (while my sister was included) in my mother’s family, since I, like most people, felt closer to her side.

We may or may not change our own names to match each others and the kids. On the one hand, sharing a family name seems really nice—it would be cool to be “the Whens”. On the other hand, I hate interacting with the government.

This is the headline result from the study cited, but looking more closely, I think actually 94% of children have only their father’s last name, with 2% having both. First, they say “(82%) reported that both husband and wife shared the same last name. Seven husbands and wives reported that they had different last names (14%), and two (4%) reported that at least one of them had hyphenated his or her last name,” which implies the 82% who shared a last name had not hyphenated. Then they say “41 of 50 (84%) of children with heterosexual parents had the same last name as both parents; six more children whose parents did not share last names had been given their fathers’ last names (12%). Altogether, 96% of children had been given their fathers’ last names.” So one of those couples where the children had the same name as both parents hadn’t been counted in the set of couples who shared a name. This is a small difference, but just wanted to point it out for the nitpickers.

It’s also surprising to me that in their sample it was more common for children to have only their mother’s name than both of their parents’ names!

Finally, I know this is a pretty small sample and it’s among adoptive parents, who differ from the general population, but the result is consistent with this 2002 study that found 97%, and it’s about what I would guess based on the people I know.

Wow, Rachel, how fantastic to read this post of yours! I think you might find my experience interesting.

I'm Brazilian and, although there are variations, the most conventional thing in Brazil is that, when a woman gets married, she adds her husband's last surname to the end of her own, whether or not she opts to erase one of the those she already had (it's more common not to erase it). The number of surnames varies - some people are born with just one, it's more usual to have two, but it's not uncommon for there to be three or even four. There isn't exactly a rule that determines which surnames will be passed on: today it's very common for children to be born with the same surnames as their mother (including the one received by her through marriage), but in the past it was more common to have the same surnames that one's father had. The only consistent rule seems to be that everyone's last name (husband, wife, children) is the same, and it's the one that originally came from the husband. In the Portuguese tradition - and unlike the Spanish tradition you mentioned - the main surname is the last one, but in practice I see this being increasingly relaxed or forgotten.

Well.. when I got married, I realized that conventional Brazilian practices led, in my case, to unsatisfactory results for more than one reason.

First of all, there was the fact that either my wife or I would have a different set of surnames from our children, as well as different ones from each other. Secondly, my first surname (the maternal one) and her second surname (the paternal one) were the same, with an extremely slight difference, which could also lead to some strange results. Finally, I didn't like the solution of her giving up both her surnames to take mine: apart from the fact that it would seem like a "colonization" of one person by another, she would have the same surnames as my brother and my mother, which would make her seem more like an adopted sister than a wife.

So we came up with a solution identical to the one you said was the most elegant, since we both had two surnames, one maternal and one paternal. In this system, the groom would replace his maternal surname (the first surname) with the bride's maternal surname, and the bride would replace her paternal surname (the second surname) with the man's paternal surname. The advantages are numerous. The whole family (man, woman and children) would have the same pair of surnames, which would be a different pair from the ones of the previous generations. As you pointed out, this system would create surnames representing the male and female lineages, and, besides this, children would also necessarily share one surname with each grandparent and each parallel cousin (besides both unmarried and parallel uncles and aunts).

In order to make things perfectly symmetrical and logical, a society following this system could agree that the first surname (the maternal surname) would be the main surname for women, and the second surname (the paternal surname) the main surname for men. This would also reduce the identity transition that is now common and troublesome when women change their surnames.

So that's what we did: we exchanged surnames. The choice came with its own costs. It turned out that, despite the elegance of the solution, my mother hated that I lost her family name. This really brought an unpleasant conflict, so sometimes I think it would have been better to have made another choice. Reading that someone else reflected on the topic and also came up with our choice as the most elegant solution brings me a little consolation, in any case.